Return to the lecture notes index

Lecture 6 (January 27, 2011)

Work, And Its Abstractions

We introduced the idea of work on the first day of class. Today we filled

in some more details about process management in distributed systems, and

dug much more deeply into threads and thread scheduling. Review the

relevant portion of the lecture notes from the first day before diving into

these. We did a brief review in class, but it is not repeated here.

Creating New Tasks

One of the functions of the operating system is to provide a mechanism for

existing tasks to create new tasks. When this happens, we call the original

task the parent. The new task is called the child. It is possible for one

task to have many children. In fact, even the children can have children.

In UNIX, child tasks can either share resources with the parent or obtain

new resources. But existing resources are not partitioned.

In UNIX when a new task is created, the child is a clone of the parent.

The new task can either continue to execute with a copy of the parent

image, or load another image. Well talk more about this soon, when we talk

about the fork() and exec-family() of calls.

After a new task is created, the parent may either wait()/waitpid() for the

child to finish or continue and execute concurrently (real or imaginary)

with the child.

Fork -- A traditional implementation

fork() is the system call that is used to create a new task

on UNIX systems. In a traditional implementation, it creates a new task

by making a nearly exact copy of the parent. Why nearly exact?

Some things don't make sense to be duplicated exactly, the ID number,

for example.

The fork() call returns the ID of the child process in the parent

and 0 in the child. Other than this type of subtle differences, the two

tasks are very much alike. Execution picks up at the same point in both.

If execution picks up at the same point in both, how can fork() return

something different in each? The answer is very straightforward.

The stack is duplicated and a different value is placed on top of each.

(If you don't remeber what the stack is, don't worry, we'll talk about

it soon -- just realize that the return value is different).

The difference in the return value of the fork() is very significant.

Most programmers check the result of the fork in order to determine

whether they are currently the child or parent. Very often the child

and parent to very different things.

The Exec-family() of calls

Since the child will often serve a very different purpose that its

parent, it is often useful to replace the child's memory space, that

was cloned form the parent, with that of another program. By replace,

I am referring to the following process:

- Deallocate the process' memory space (memory pages, stack, etc).

- Allocate new resources

- Fill these resources with the state of a new process.

- (Some of the parent's state is preserved, the group id,

interrupt mask, and a few other items.)

Fork w/copy-on-write

Copying all of the pages of memory associated with a process is a

very expensive thing to do. It is even more expensive considering that

very often the first act of the child is to deallocate this recently

created space.

One alternative to a traditional fork implementation is called

copy-on-write. the details of this mechanism won't be completely

clear until we study memory management, but we can get the flavor now.

The basic idea is that we mark all of the parent's memory pages as

read-only, instead of duplicating them. If either the parent or

any child try to write to one of these read-only pages, a page-fault

occurs. At this point, a new copy of the page is created for the writing

process. This adds some overhead to page accesses, but saves us the

cost of unnecessarly copying pages.

vfork()

Another alternative is also available -- vfork(). vfork is even

faster, but can also be dangerous in the worng hands. With vfork(),

we do not duplicate or mark the parent's pages, we simply loan them, and

the stack frame to the child process. During this time, the parent

remains blocked (it can't use the pages). The dangerous part is this:

any changes the child makes will be seen by the aprent process.

vfork() is most useful when it is immediately followed by an exec_().

This is because an exec() will create a completely new process-space,

anyway. There is no reason to create a new task space for the child,

just to have it throw it away as part of an exec(). Instead, we can

loan it the parent's space long enough for it to get started (exec'd).

Although there are several (4) different functions in the exec-family,

the only difference is the way they are parameterizes; under-the-hood,

they all work identically (and are often one).

After a new task is created, the parent will often want

to wait for it (and any siblings) to finish. We discussed the

defunct and zombie states last class. The wait-family of

calls is used for this purpose.

The Conceptual Thread

In our discussion of tasks we said that a task

is an operating system abstraction that represents the state of a

program in execution. We learned that this state included such things as

the registers, the stack, the memory, and the program counter, as well

as software state such as "running," "blocked", &c. We also said that

the processes on a system compete for the systems resources, especially

the CPU(s).

Today we discussed another operating system abstraction called the

thread. A thread, like a task, represents a discrete piece

of work-in-progress. But unlike tasks, threads cooperate in their

use of resources and in fact share many of them.

We can think of a thread as a task within a task. Among other things

threads introduce concurrency into our programs -- many threads

of control may exist. Older operating systems didn't support

threads. Instead of tasks, they represented work with an abstraction

known as a process. The name process, e.g. first do ___,

then do ____, if x then do ____, finally do ____, suggests only

one thread of control. The name task, suggests a more general

abstraction. For historical reasons, colloquially we often say

process when we really mean task. From this point

forward I'll often say process when I mean task --

I'll draw our attention to the difference, if it is important.

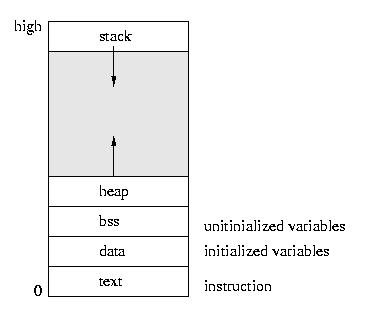

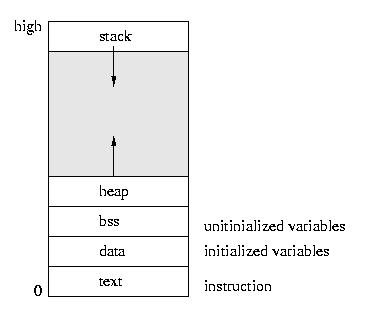

A Process's Memory

Before we talk about how a tasks' memory is laid out, let's

first look at the simpler case of a process -- a task with

only one thread of control.

Please note that the heap grows upward through dynamic allocation

(like malloc) and the stack grows downward as stack frames are

added throguh function calls. Such things as return addresses, return

values, parameters, local variables, and other state are stored in

the runtime stack.

- The text area holds the program code.

- The data area holds global and static variables that must be

stored in the executible, since they are initialized.

- The bss area holds variables that are unitialized in the sense

that their need not be persistently stored on disk -- they can be

plugged in later.

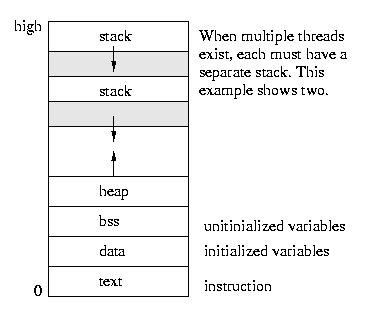

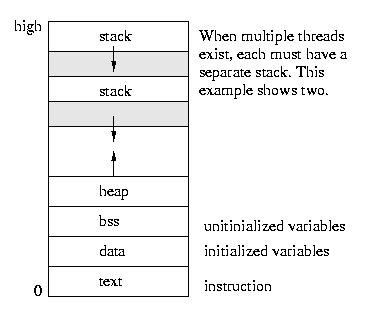

The Implementation of Threads

All of the threads within a process exist within the context of that

process. They share the code section, data section, and operating system

resources such as open files.

But they do not share all resources. Since each thread executes

independently, each thread has its own understanding of the stack and of

the registers.

The good part about sharing so many resources is that switching

execution among threads is less expensive than it is among processes.

The bad part is that unlike the protection that exists among processes,

the operating system can not prevent threads from interfering with each

other -- they share the same process space.

Kernel Threads

The most primitive implementations of threads were invisible to the

user. They existed only within the kernel. Many of the kernel daemons,

such at the page daemon, were implemented as threads. Implementing

different operating system functions as threads made sense for many

reasons:

- There was no need for protection, since the kernel developers trust

themselves. Please note that we lose memory protection

once we go from processes to threads -- they all play in the

same address space.

- The different OS functions shared many of the kernel's resources

- They can be created and destroyed very cheaply, so they can be

easily used for things like I/O requests and other intermitent

activities.

- It is very cheap to switch among them to handle various tasks

- It is very easy to thing of kernel activities in terms of

separate threads instead of functions within one monolithic

kernel.

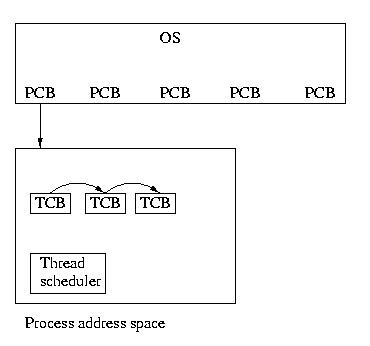

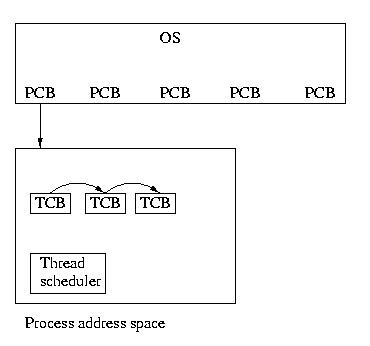

User Threads

But the UNIX developers couldn't keep such a great thing as their own

private secret for long. Users began to use threads via thread

libraries. Thread libraries gave users the illusion of

threads, without any involvement form the kernel. When a process

containing threads is executed, the thread scheduler, within the process,

is run. This scheduler selects which thread should run and for how long.

If a thread should block, the scheduler can select to run another thread

within the same process.

This implementation of threads is actually much more than an illusion. It

gives users the ability to write very efficient programs. These programs

can switch among threads and share resurces with very little overhead.

To switch threads, the registers must be saved and restored and the

stack must be switched. No expensive context switch is required.

Another advantage is that user level threads are implemented entirely

by a thread library -- from the interface to the scheduling. The kernel

doesn't see them or know about them.

Kernel-Supported User-Level Threads

Kernel threads are great for kernel writers and user threads answer many

of the needs of users, but they are not perfect. Consider these examples:

- On a multiprocessor system, only one thread within a process

can execute at a time

- A process that consists of many threads, each of which may be

able to execute at any time, will not get any more CPU time

than a process containing only one thread

- If any thread within a process makes a system call, all threads

within that process will be blocked because of the context switch.

- If any user thread blocks waiting for I/O or a resource, the entire

process blocks. (Thread libraries usually replace blocking calls

with non-blocking calls whenever possible to mitigate this.)

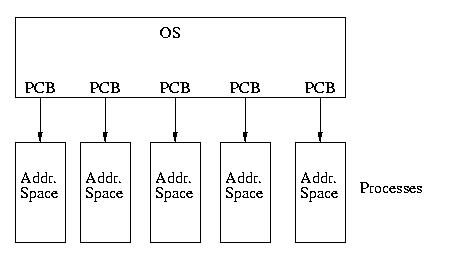

To address these needs, we need to have a kernel supported user thread.

That is to say, we need a facility for threads to share resources within

a process, but we also need the ability of the kernel to preempt, schedule,

and dispatch threads. This type of thread is called a kernel supported

user thread or a light-weight process (LWP). A light-weight

process is in contrast with a heavy-weight process otherwise known

as a process or task.

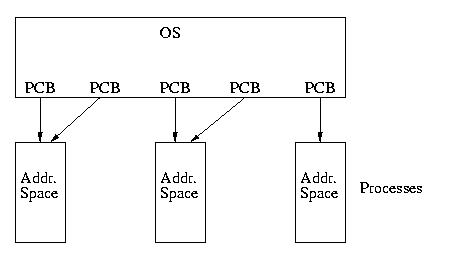

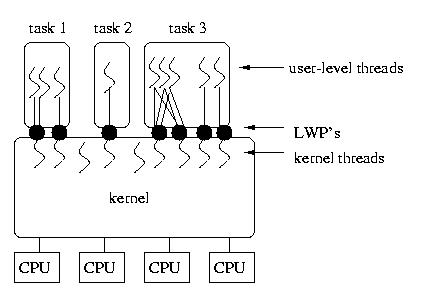

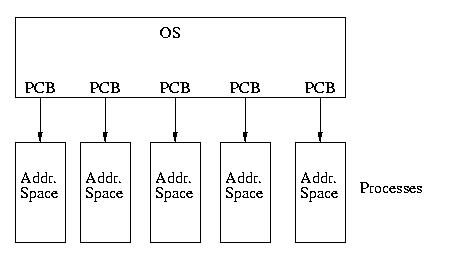

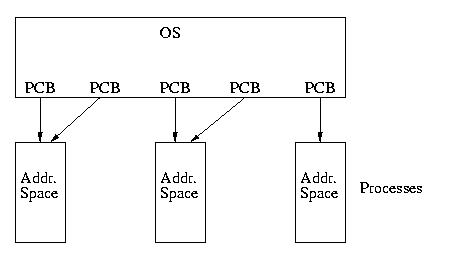

Our model of the universe has gone from looking like this:

To looking like this:

A More Complex Model

In some models, such as that used by Solaris, it is also possible to

assign several kernel-supported threads to a single process without

assigning them to specific user-level threads. In this case, the process

will have more opportunities to be seen by the OS's CPU scheduler. On

multiprocessor systems, the maximum level of concurrency is determined

by the number of LWPs assigned to the process (of course this is further

limited by the number of threads that are runnable within the process

and the number of available CPUs).

In the context of

Solaris, an LWP is a user-visible kernel thread. In some ways, it

might be better to view a Solaris LWP as a virtual light weight

processor (this is Kesden nomenclature!). This is because pools

of LWPs can be assigned to the same task. Threads within that task are

then scheduled to run on available LWPs, much like processes are scheduled

to run on available processors.

In truth, LWPs are anything but light weight. They are lighter weight

than (heavy weight) processes -- but they require far more overhead

than user-level threads without kernel support. Context-switching among

user-level threads within a process is much, much cheaper than context

switching among LWPs. But, switching among LWPs can lead to greater

concurrency for a task when user-level threads block within the kernel

(as opposed to within the process such that the thread scheduler can run

another).

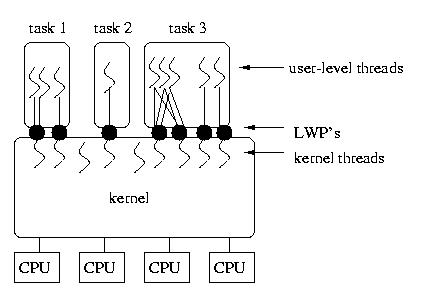

The diagram below shows LWP's associated with tasks and kernel threads, as

well as kernel threads without an associated LWP and several different

associations between user-level threads and the LWP(s) assigned to the

process.

LWP's offer a convenient and flexible compromise between user-threads and

separate processes. But it is important to realize that they are bulky

structures:

- Communications, even within a process, among LWPs requires

kernel involvement (read as: 2 context switches)

- LWPs are scheduled by the kernel, so blocking an LWP requires

kernel involvement.

- LWPs are very flexible, and very general -- this means that they

are very big. LWPs consume a great deal of resources

- LWPs are expensive to create and destroy, because this involves

the kernel

- LWPs are unpoliced, so users can create many of them, consuming

system resources, and starving other users processes by

getting more CPU time than similar processes with fewer LWPs.

Another Model

You might observe that threads within the same task share many of the

same resources -- the most significant difference is that they have

different stacks. This is exactly how Linux implements threads --

by leveraging the machinery it uses to create new processes.

In Linux, the system call beneath a fork() is known as clone(). It does

everything that fork() does -- but wiht a lot more flexibility. It allows

a newly created child to be created from the template of its parent by

either copying, sharing, or recreating various resources from the parent.

So, you can imagine that if all of the important resources are copies --

clone() is, in effect, a fork().

But, imagine two different processes that, in essence, share everything

but the stack. These processes are sharing global memory, so they are

really in the smae memory context -- but they have differnt stacks, so

can be doing different things. They are, in effect, threads.

So, as Linux evolved, they created kernel-supported threads by leveraging

clone() to create new processes that shared resources. They then created

a new task abstraction that aggregated related processes. So, in the

Linux model, within the kernel, a task is genuinely a collection of

processes. From the user's perspective, these thread-like processes

are presented as threads by the user-level thread library.

Tasks in Distributed Systems

In distributed systems, we find that the various resources needed to

perform a task are scattered across a network. This blurs the distinction

between a process and a task and, for that matter, a task and a thread.

In the context of distributed systems, a process and a thread

are interchangable terms -- they represent something that the user wants

done.

But, task has an interesting and slightly nuianced meaning. A

task is the collection of resources configured to solve a

particular problem. A task contains not only the open files and

communication channels -- but also the threads (a.k.a. processes).

Distributed Systems people see a task as the enviornment in which

work is done -- and the thread (a.k.a. process) as the instance of

that work, in progress.

I like to explain that a task is a factory -- all of the means of production

scattered across many assembly lines. The task contains the machinery and

the supplies -- as well the processes that are ongoing and making use of them.

Although this is traditionally a Distributed Systems view of the world, it

it is pretty applicable to modern operating systems that implement

kernel-supported threads, whether by a Linux-style close() or a Solaris-style

first-class task abstraction.

Scheduling Basics

Scheduling the access of processes to non-sharable resources is a

fundamental part of an operating system's job. The same is

true of the thread scheduler within a user-level thread library.

The CPU is the most important among these resource, because it typically

has the highest contention. The high cost of additional CPUs, both in terms

of the price of the processor and the cost of the technology in massively

parallel systems, ensures that most systems don't have a sufficient surplus

of CPUs to allow for their wasteful use.

The primary objective of CPU scheduling is to ensure that as many jobs

are running at a time as is possible. On a single-CPU system, the goal

is to keep one job running at all times.

Multiprogramming allows us to keep many jobs ready to run at all times.

Although we can not concurrently run more jobs than we have available

processors, we can allow each processor to be running one job, while

other jobs are waiting for I/O or other events.

Observation: The CPU-I/O Burst Cycle

During our discussion of scheduling, I may make reference to the

CPU-I/O burst cycle. This is a reference to the observation that

programs usually have a burst of I/O (when the collect data) followed

by a burst of CPU (when they process it and request more). These bursts

form a cycle of execution.

Some processes have long bursts of CPU usage, followed by short bursts of

I/O. We say that thee jobs are CPU Bound.

Some processes have long bursts of I/O, followed by short bursts of

CPU. We say that thee jobs are I/O Bound.

The CPU Scheduler

Some schedulers are only invoked after a job finishes executing or

voluntarily yield the CPU. This type of scheduler is called a

non-premptive scheduler.

- A process blocks itself waiting for a resource or event

- A process terminates

But, in order to support interaction, most modern schedulers are

premeptive. They make use of a hardware timer to interrupt running

jobs. When a scheduler hardware interrupt occurs, the scheduler's

ISR (Interrupt Service Routine) is invoked and it runs. When this happens, it can continue the

previous task or run another. Before starting a new job, the

scheduler sets the hardware timer to generate an interrupt after

a particular amount of time. This time is known as the time

quantum. It is the amount of time that a job can run without

interruption.

A preemptive scheduler may be invoked under the following four

circumstances:

- A process blocks itself waiting for a resource or event

- A process terminates

- A process moves from running to ready (interrupt)

- A process moves from waiting to ready (blocking condition satisfied)

The Dispatcher

Once the CPU scheduler selects a process for execution, it is the job of

the dispatcher to start the selected process. Starting this process

involves three steps:

- Switching context

- Switching to user mode

- Jumping to the proper location in the program to start or

resume execution

The latency introduced by the dispatch is called the dispatch

latency. Obviously, this should be as small as possible -- but is

most critical in real-time system, those systems that must

meet deadlines associated with real world events. These systems are

often associted with manufacturing systems, monitoring systems, &c.

Actually, admission is also much more important in these systems --

a job isn't automically admitted, it is only admitted if the system

can verify that enough resources are available to meet the deadlines

associated with the job. But real-time systems are a different story

-- back to today's tale.

Scheduling Algorithms

So, given a collection of tasks, how might the OS (or the

user-level thread scheduler) decide which to place on an available CPU?

First Come, First Serve (FCFS)

First In, First Out (FIFO)

FCFS is the simplest algorithm. It should make sense to anyone who has

waited in line at the deli, bank, or check-out line, or to anyone

who has ever called a customer service telephone number, "Your

call will be answered in the order in which it was received."

The approach is very simple. When a job is submitted, it enters the ready

queue. The oldest job (has been in the ready queue for the longest time)

in the ready queue is always selected to be dispatched. The algorithm is

non-premptive, so the job will run until it voluntarily gives up the CPU

by blocking or terminating. After a blocked process is satisfied and

returns to the ready queue, it enters at the end of the line.

This algorithm is very easy to implement, and it is also very fair and

consequently starvation-free. No characteristic of a job bias its

placement in the queue. But it does have several disadvantages.

- Because short jobs can be scheduled after very long jobs,

the average wait time can be increased. Unlike the grocery

store, the algorithm has no "Express Lane."

- Since the algorithm is non-premptive, there can be problems

on interactive systems. A long job may prevent responsiveness

to the user.

- A student actually pointed out this more subtle property

during class in the form of a question (good job!)

It is possible for one CPU bound process to hog the CPU for

a long time. In the meantime several I/O bound processes, that

could execute concurrently with the CPU-bound process, can't

start.

I didn't give this phenomenon a name in class, but

I probably should have -- it is called the convoy effect,

because cycle after cycle, the I/O bound processes will "follow"

the CPU bound processes, without overlapping.

Bonus Material

Everything in this section goes above and beyond lecture. It is just here

for those who happen to be curious for more real-world detail.

Shortest-Job-First (SJF)

Another apporach is to consider the expected length of each processes's

next CPU burst and to run the process with the shortest burst next. This

algorithm optimizes the average waiting time of the processes. This is

because moving a shorter job ahead of a longer job helps the shorter

job more than it hurts the longer job. Recall my lunchroom story --

those who ate early had no lines, although there wasn't anyone to

vouch for this.

Unfortunately, we have no good way of knowing for sure the length of any

jobs next CPU burst. In practice this can be estimated using an exponential

average of the jobs recent CPU usage. In the past, programmers estimated

it -- but if their jobs went over their estimate, they were killed.

programmers got very good at "The Price Is Right."

Sometimes this algorithm is premeptive. A job can be prempted if another

job arrives that has a shorter execution time. This is flavor is often

called shortest-remaining-time-first (SRTF).

Shortest-Time-To-Completion-First (STCF)

Shortest CPU time to Completion First (STCF). The process that will

complete first runs whenever possible. The other processes only run

when the first process is busy with an I/O event.

But, much like SJF, the CPU time is not known in advance.

Priority Scheduling (PRI)

Priority scheduling is designed to strictly enforce the goals of a system.

Important jobs always run before less important jobs. If this scheduling

discipline is implemented preemeptively, more important jobs will preempt

less important jobs, even if they are currently running.

The bigest problem with priority-based scheduling is starvation.

it is possible that low priority jobs will never execute, if more

important jobs continually arrive.

Round Robin Scheduling (RR)

Round Robin scheduling can be thought of as a preemptive version of FCFS.

Jobs are processed in a FCFS order from the run queue. As with FCFS,

if they block, the next process can be scheduled. And when a blocked

process returns to the ready queue, it is placed at the end of the list.

The difference is that each process is given a time quantum or

time slice. A hardware timer interrupt preemept the running

process, if it is still running after this fixed amount of time.

The scheduler can then dispatch the next process in the queue.

With an appropriate time quantum, this process offeres a better

average case performance than FCFS without the guesswork of SJF.

If the time quantum is very, very small, an interesting effect is

produced. If there are N processes, each process executes as if

it were running on its own private CPU running at 1/N th the speed.

This effect is called processor sharing.

If the time quantum is very, very large -- large enough that the

processes generally complete before it expires, this approach

approximates FCFS.

The time quantum can be selected to balance the two effects.

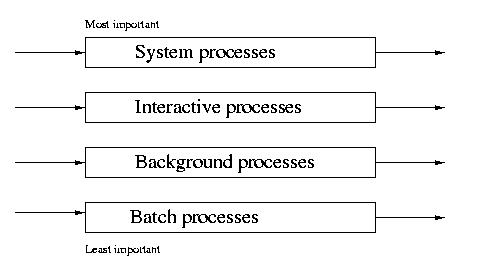

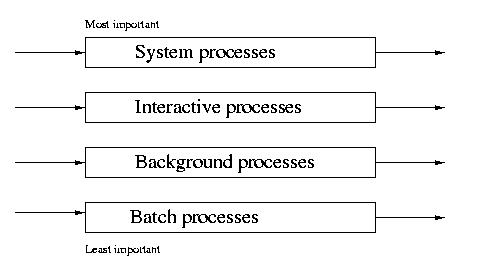

Multilevel Queue Scheduling (MQS)

MQS is similar to PRI, except that the jobs arrive sorted by their

priority. For example, all system jobs may have a higher priority than

interactive jobs, which enjoy a higher priority than batch jobs.

Jobs of different priorities are placed into different queues.

In some implementations, jobs in all higher priority queues must be

executed before jobs in any lower priority queue. This absolute approach

can lead to starvation in the same way as its simplier cousin, PRI.

In some preemptive implementations, a lower-priority process will be

returned to its ready queue, if a higher-priority process arrives.

Another approach is to time-slice among the queues. Higher priority

queus can be given longer or more frequent time slices. This approach

prevents absolute starvation.

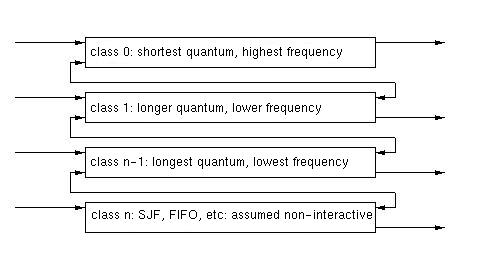

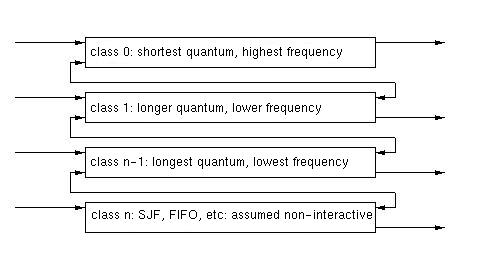

Multilevel Feedback Queue (MFQ)

In the multilevel queuing system we described above, there is no social

mobility. When aprocess arrives, it is placed in a queue based on its

initial classification. It remains in this queue throughout its lifetime.

In a MFQ system, a process's priority can change as the result of its CPU

utilization. Processes that have longer CPU bursts are lowered in

importance. Processes that are I/O bound and frequently release the CPU

prematurely by blocking are increased in importance.

This system prevents starvation and gives I/O bound processes the change

to be dispatched and overlap with CPU bound processes. It fights the

convoy effect.

Scheduling among queues can be done by varying the lenght or frequence

of the time slice. Scheduling within each queue can also be varied.

Although this system sounds very pretty, it is very complex. In general

this type of system is defined by the following parameters:

- the number of queues

- the method of scheduling for each queue

- the method of scheudling among the queues

- the method of promoting a process

- the method of demoting a process

Traditional UNIX Scheduling - Introduction

I thought it would be interesting to spend some time considering

scheduling in a real-world operating system. Today we'll talk about what

I call "traditional" UNIX scheduling. This scheduling system was used,

with little variation through AT&T SVR3 and 4.3BSD. Newer UNIX's use

more sophisticated approaches, but this is a good place to start.

Priorities

The scheduling in these systems was priority based. The priority of a

process ranged from 0 - 127. Counterintuitively, lower priorities

represent more important processes.

The range of priorities is partitioned. Priorities in the range of

0 - 49 are reserved for system processes. Both user and system processes

may have priorities over the full range from 0 - 127. Ths prevents

user processes from interfereing with more important system tasks.

Parameters

A processes ultimate scheduling priority varies with several factors.

The accounting of these factors is kept in the proc structure,

which contains the following fields:

- p_pri - current scheduling priority

- p_usrpri - the process's priority in user mode

- p_cpu - a measure of the prcoess's recent CPU usage

- p_nice - a user supplied measure of the process's importance.

Elevated Priority in System Mode

p_pri is a number in the range of 0 - 127 that represents the

priority of the process. This is the value of that the scheduler considers

when selecting a process to be dispatched. This value is normally the

same as p_usrpri. It however, may be lowered (making the process more

important) while the process is making a system call.

Traditional UNIX systems did not have preemptive kernels. This meant that

only one process could be in the kernel at a time. If a process blocked

while in a system call, other user processes could run, but not other

system calls or functions. For this reason a process which had blocked

while in a system call often would have its p_pri value lowered so

that it would expeditiously complete its work in the kernel and return

to user mode. This allowed other processes that blocked waiting to enter

the kernel to make progress. Once the system call is complete, the

process's p_pri is reset to its p_usrpri.

User Mode Priority

The priority that a process within the kernel receives after returning

from the blocked queue is called its sleep priority. There is

a specific sleep priority associated with every blocking condition.

For example, the sleep priority associated with terminal I/O was

28 and disk I/0 was 20.

The user mode scheduling priority depends on three factors:

- the default user mode priority, PUSER, typically 50

- the process's recent CPU usuage, p_cpu

- the nice value assigned by the user, p_nice

The p_usr value is a system-wide default. In most implementations it

was 50, indicating the most important level of scheduling for a user

process.

Let's be Nice

The p_nice value defaults to 0, but can be increased by users who

want to be nice. Remember that the likelihood of a process to be dispatched

is inversly proportional to the priority. By increasing the process's

nice value, the process is deacreasing its likelihood of being scheduled.

Processes are usually "niced" if they are long-running, non-interactive

backgorund processes.

Tracking CPU usage

p_cpu is a measure of the process's recent CPU usage. It ranges from

0 - 127 and is initially 0. Ever 1/10th of a second, the ISR that handles

clock ticks increments the p_cpu for the current process.

Every 1 second another ISR decreases the p_cpu of all processes, running

or not. This reduction is called the decay. SVR3 used a fixed

decay of 1/2. The problem with a fixed decay is that it elevates the

priority of nearly all processes if the load is very high, since very

few processes are getting CPU. This makes the p_cpu field nearly meaningless.

The designers of 4.3BSD remedied this side-effect by using a variable decay

that is a fuction of the systems load average, the average number

of processes in the run queue over the last second. This formula follows:

decay_factor = (2*load_average)/ (2*load_average + 1)

User Mode Priority - Final Formula

The scheduler computes the process's user priority form these factors

as follows:

p_usrpri = PUSER + (p_cpu/4) + (2*p_nice)

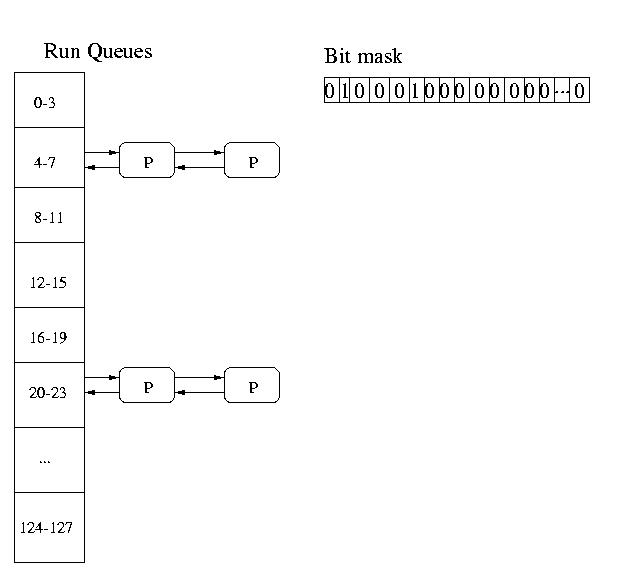

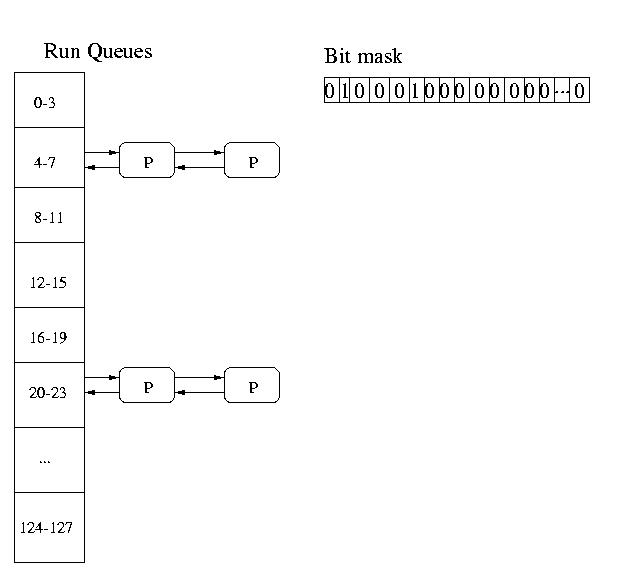

Implementation

Artifacts of the old DEC VAX systems made it much more efficient

to collapse the 127 priorities into 32 queues. So these systems

in effect had 32 queues each holding processes in a range of

4 priority levels (0-3, 4-7, 8-11, 12-15, 16-19, etc).

The system maintained a 32-bit mask. Each bit represented a single

queue. If the bit was set, there were jobs in the queue. If the bit was 0,

the queue was empty. The system charged from low-bit to high-bit in this

mask until it found a non-empty queue. It would then select a job

Round Robin (RR) from this queue to be dispatched.

The round-robin scheduling with a time quantum of 100mS only applied to

processes in the same queue. If a process arrived in a lower priority

(more important) queue, that process would be scheduled at the end

of the currently executing process's quantum.

High priority (less important) processes would not execute until all

lower priority (more important) queues were empty.

The queues would be check by means of the bit mask every time a process

blocked or a time quantum expired.

Analysis

This method of scheduling proved viable for general purpose systems,

but it does have several limitations:

- it falls apart with a massive number of processes - the

overhead of recomputing priorities for every process every second

becomes too high

- nice values are a very weak and underutilized way for applications

to affect their priorities -- how often doyou nice your jobs?

- A non-preemptive kernel means that important processes may have to

wait for lower priority processes in the kernel. The temporary

sleep priority is a weak solution.