Anti-Dilution Protection Postscript

At the risk of beating a dead horseÉ

LetÕs summarize where weÕve been in recent weeks.

An investor in any given round of financing is concerned that the next round could be at a lower price per share than what he is paying this round. Therefore, the investor will insist upon anti-dilution protection.

In recent weeks, we have discussed the two common types of anti-dilution protection: full ratchet and weighted average. In the event that the current round of investment is at a lower price per share, then:

á Full ratchet anti-dilution protection gives the original investor rights to that number of shares of common stock as if he paid the current roundÕs lower price.

á Weighted average anti-dilution protection gives consideration to the relationship between the total number of shares outstanding compared to the number of shares held by the original investor.

You will prefer weighted average anti-dilution protection to full ratchet.

While I know that several readers will not believe this, but what IÕve done in prior weeks is to try to simplify the calculations involved in the explanations of the various forms of anti-dilution protection.

This week I will introduce one of the primary components of complexity – the treatment of stock options.

Fully Diluted Basis

The strict definition of fully diluted basis is:

Number of shares of Common Stock deemed to be outstanding

immediately prior to new issue (includes all shares of outstanding common

stock, all shares of outstanding preferred stock on an as-converted basis, and

all outstanding options on an as-exercised basis; and does not include any

convertible securities converting into this round of financing).

In essence, an investor will phrase the terms of his investment as being calculated on a Òfully diluted basis,Ó by including shares of common stock that are not currently outstanding, but the company is obligated to issue them based upon existing agreements (convertible preferred stock, options, etc.). The inclusion of these numbers in the share base can significantly impact the resulting outcomes.

LetÕs take a look at how option pools can impact full ratchet anti-dilution protection.

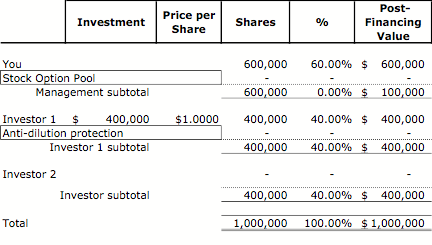

The First Round

LetÕs review the example that weÕve been using in this series of articles.

á I offer to invest $400,000 in your company in exchange for 40% of it.

á Since you own all 600,000 shares of your company, I am offering to buy 400,000 new shares in order to acquire 40%.

á My investment of $400,000 divided by 400,000 shares that IÕm buying yields a per share price of $1.00.

á Since you own 600,000 shares, that means the value of the stake in your company is $600,000, which is the pre-financing value.

á Adding my $400,000 to that yields a post-financing value of $1,000,000.

á That is confirmed by taking the total number of outstanding shares, 1,000,000 (your 600,000 and my 400,000) and multiplying that by the share price of $1.00.

á That also says that the post-financing value of your company is $1,000,000.

The terms of this deal include full ratchet

anti-dilution protection for me.

The Second Round

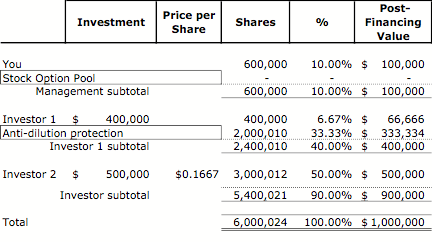

ItÕs time to raise some more money. Unfortunately, the only investment offer you are able to attract is at a lower price per share than the prior round.

á The new investor offers to invest $500,000 for 50% of your company.

Since I have full ratchet anti-dilution protection; that has to be included in the calculations.

As I noted in the original article, the full ratchet anti-dilution protection creates a pretty ugly outcome for you.

The Investor Outcome

The share price drops all the way to less than $0.17.

The new investor buys 3,000,012 shares.

I get 2,000,010 shares as a result of full ratchet anti-dilution protection.

Your Outcome

All of these adjustments have occurred to the investorsÕ positions. What happens to you?

It isnÕt pretty. As the number of shares for the investors ratchet higher and higher, your number of shares remains constant at 600,000.

Your share of

your company has fallen to 10%!

The value of your

shares has dropped to $100,000!

ButÉ

As a practical matter, the investor in Round 2 would not do

the deal without a provision for a management option pool. LetÕs say that the

investor call for a 9% pool. That gives us several values for variables that

will allow us to calculate the resulting capitalization table.

- You

own 600,000 shares of common stock.

- I

have invested $400,000 with full ratchet anti-dilution protection.

- The

new investor has agreed to invest $500,000 for 50% of the company on a

fully diluted basis after provision for a 9% option pool.

LetÕs take a look at the outcome.

The Investor Outcome

The share price drops all the way to less than $0.02.

The new investor buys 30,000,000 shares.

I get 23,600,000 shares as a result of full ratchet anti-dilution protection.

Your Outcome

All of these adjustments have occurred to the investorsÕ positions. What happens to you?

It is pretty ugly. As the number of shares for the investors have ratcheted higher and higher, your number of shares remains constant at 600,000.

Your share of your company has fallen to 1%!

The value of your shares has dropped to $10,000!

Reviewing the Basics

LetÕs look at some of the relevant basics.

á Deals are negotiated with percentages, but are structured with shares.

á The value of a company is determined by multiplying the total number of common shares by the most recent share price.

á Price per share = Amount of investment divided by the number of shares purchased.

As IÕve said before, these may appear to be pretty dry and

boring gobblygook, but as weÕve seen, they can have very significant

consequences.

Recap

An investor will invest on a fully diluted basis.

Avoid any deal that has a non-diluted fixed percentage of the equity.

If thatÕs unavoidable, at least negotiate for conditions under which that restriction goes away.

Well, thatÕs about it

for anti-dilution protection. Next week weÕll move on to something else.

Whew!

Frank Demmler

is Associate Teaching Professor of Entrepreneurship at the Donald H. Jones

Center for Entrepreneurship at the Tepper School of Business at Carnegie Mellon

University. Previously he was president & CEO of the Future Fund, general

partner of the Pittsburgh Seed Fund, co-founder & investment advisor to the

Western Pennsylvania Adventure Capital Fund, as well as vice president, venture

development, for The Enterprise Corporation of Pittsburgh. An archive of this

series of articles can be found at my

website.