|

| Frank Patrick Herbert (1920-1986):

newspaperman, cameraman, radio commentator, oyster-diver, judo instructor,

jungle survival instructor, lay analyst, Navy photographer, serious amateur

scientist, ecologist, Tacoma native, Seattle Mariners fan and second-tier

science fiction writer. |

I don’t read it often, but I find that

there’s often an odd, surreal quality to what gets reported in USA Today.

Many years back, I remember a boxed story in the sports section with a

picture of a forgotten pitcher (a Seattle Mariner, I think). The heading

was something like “Joe Blow’s Five Favorite Frank Herbert Novels.” For

the non-science fiction fans out there, Frank Herbert is best known for

his novel Dune (but see link for many other books), which was followed

by a series of sequels (Dune Messiah,

Children of Dune, etc.).

Turns out the pitcher’s five favorite Frank Herbert novels were, in order:

|

Dune

Dune Messiah

Children of Dune

another Dune sequel

another Dune sequel

|

With the possible exception of Arrakis,

the desert world on which much of Dune takes place, on what planet

does that qualify as news, let alone sports news? |

|

|

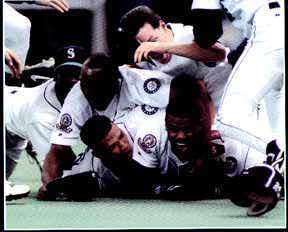

Seattle Mariners argue over

the best Frank Herbert novel

|

|

I was reminded of the top five

Dune novels last week when I unexpectedly found myself in Columbia,

South Carolina for three days. The hotel where I was staying delivered

USA Today to my room every morning, and I awoke one morning to find

that the lead headline in the paper was “Food Pyramid Challenged.” Under

the headline, it was reported that “Harvard nutrition expert says the government’s

model is outdated and perhaps ill-conceived.” You can see why that would

be the lead story for the entire country—there’s nothing more electrifying

than a claim that a government policy is “perhaps ill-conceived.”

|

|

Take two bananas and call

me in the morning

|

| Then again, I don’t pay much attention

to the latest “what food’s good for you” news stories anyway since we seem

to get a fair amount of conflicting advice: should I drink more red wine?

put olive oil on everything? To be fair, there seems to be general agreement

that the basic western diet—lots of fats and sweets—is bad for you, and

that news seems to have had limited impact on eating habits. (And not just

bad for us: studies of baboons in eastern Africa found that troops that

discovered garbage dumps near tourist lodges consumed more calories and

matured faster, but also had substantially higher levels of cholesterol

and insulin than their savanna-foraging cousins.) |

Why can’t medical researchers get

their stories straight about what we should be eating? I don’t actually

know, but I’m sympathetic. Economists get criticized for a similar inability

to nail down the answers to some basic questions: what is the effect of

a minimum wage on unemployment, for example. Economists have a good answer:

the world is complicated, and it’s often hard to isolate individual effects

in a complicated world (I suspect medical researchers have a similar answer).

|

|

How to identify with economists

|

|

|

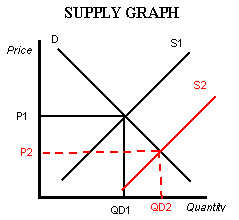

| One of the most difficult issues

that economists who analyze data have to contend with is known as the “identification

problem.” Here’s a standard version of the problem. Suppose that you want

to know what will happen to sales of a product if its price were to increase

by five percent. You can go out and collect information on, say, monthly

sales and prices of the product over the last five years, and use that

to estimate the relationship between price and units sold. You’d probably

expect to find a negative relationship—if prices are high, sales will be

low. Unfortunately, the world tends to be more complicated than that. Think

of the standard-issue supply and demand chart: price on the vertical axis,

sales on the horizontal axis, demand slopes down, supply slopes up; market

price and quantity is where the two curves intersect. (You may want to

find a piece of scratch paper and pencil at this point.) Suppose that during

the period you’re studying, costs are shifting. Cost shifts mean that the

supply curve is shifting left or right over time. If the supply curve shifts

left, the intersection points occurs at a higher price and lower sales—what

you were probably expecting. |

| But suppose instead that costs

are unchanged, but demand for the product increases. Then the demand

curve shifts right, so the intersection of supply and demand takes place

at a higher price and higher sales. So now higher prices are associated

with higher, not lower, sales. The problem is that if the supply curve

is shifting, points on the demand curve are traced out, but if the demand

curve is shifting, points on the supply curve are traced out. In the first

case, the demand curve is “identified;” in the second, you can “identify”

the supply curve. In general, though, both supply and demand curves can

be shifting at the same time, and it can be difficult to disentangle the

two effects. That’s the “identification” problem. |

| Identification problems show up

throughout empirical economics. Another classic example arises in the “human

capital” literature. Suppose you want to know the effect of an extra year

of school on wage rates. You could collect information on individuals’

earnings and years of schooling and estimate the relationship between the

two. But there’s a problem—the people who got a lot of schooling are not

a random sample of all workers—in general, people with more schooling stay

in school for a reason. And one reason is that school may be a better investment

for “high ability” workers than for “low ability” workers. If that’s the

case, then the premium that workers with high levels of schooling receive

over others will reflect both the effect of additional schooling as well

as higher average ability levels—in other words, those workers may have

earned more even if they had stayed in school no longer than the low-schooling

group. |

| So how do you disentangle the effects

of ability on wages from the effect of schooling? How do you solve the

identification problem? The statistical issues that have to be dealt with

can get extremely technical and complicated, but economists also have been

ingenious in finding “natural experiments” that allow them to deal with

the identification problem. The problem for school-earnings analyses is

that for any individual, years of schooling likely is related to ability,

which likely will influence wages. But in certain circumstances, years

of schooling probably is not related to ability. One study, for example,

looks at US students who received only the minimum amount of schooling.

Suppose that schooling is mandatory until the age of 16, and that a child

must begin school if he or she turns six before September 1. Now consider

the group of kids who left school at 16. Those kids born before September

1 will have received 10 years of schooling, but those born after September

1 will have stayed in school only nine years. To the extent there’s no

relationship between ability levels and date of birth, the kids born after

September 1 will have the same average ability level as those born before,

but one less year of schooling. This difference can be exploited to estimate

the effect of an additional year of schooling on wages. Because years of

schooling is unlikely to be related to ability in that group of workers,

the effects of schooling and ability can be disentangled—the schooling

effect is identified. (Another approach is to use identical twins with

different levels of education to estimate the effect of schooling.) |

Fortunately, new statistical techniques

continue to be developed, and new and better data sources continue to become

available, so we’re likely to witness continued progress in the economic

analyses of empirical questions in the years ahead. Not to mention continued

progress on the food pyramid front. In the meantime, eat sensibly and exercise

regularly.

|

|

References

|

| The effect of diet on wild baboons

is discussed in Robert M. Sapolsky, “Junk Food Monkeys,” in The Trouble

with Testosterone and Other Essays on the Biology of the Human Predicament,

1997. The identification problem in human capital and other studies is

discussed in Mark R. Rosenzweig and Kenneth I. Wolpin, “Natural ‘Natural

Experiments’ in Economics,” Journal of Economic Literature, December

2000. |