|

|

| As 1997 began, most economists [in Britain] agreed: the year would bring rapid growth in GDP, and interest rates would have to rise, just after the general election if not before, to keep down inflation. In recent weeks this consensus has started to break down . . . |

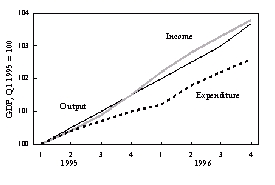

| Doubts about the quality of data are obscuring the view. The Office for National Statistics calculates three different measures of GDP, based on inputs, outputs and expenditures. In theory, these should be equal; in practice, they rarely are. This is not too surprising. Measuring the total activity of an economy is a complex task. As our chart shows, currently the gap between these measures is large. In the year to the third quarter of 1996, the income-based measure of GDP grew by 2.8%, the output-based measure by 2.5%, and the expenditure-based measure by only 1.8%. |

| Tim Congdon, an economist at Lombard Street Research, reckons that, if the income-based measure is right, the economy may be growing close to capacity, in which case inflation will rise early in 1988. But if instead the expenditure measure is right (which he doubts), the economy can grow for a few quarters before inflation becomes a problem. When a similar divergence occurred in the mid-1980s, policymakers focused on the lower expenditure measure, and thus failed to spot the impending boom. |

Measured GDP in the United Kingdom, Jan 1995 - Dec 1996 |